Language is just language until it isn't: Nigeria's Nollywood makes a Korean movie as America's Hollywood shoots to portray Igbo culture

how can we culturally interact beyond the global model of superpower domination?

One fine Saturday, I opened TikTok to find the unexpected: a Nigerian-Korean movie titled My Sunshine released, featuring an all-Nigerian cast.

I won’t go into the plot because there wasn’t much to it other than a representation of the typical high school romance tropes prevalent in Kdramas like Boys over Flowers and The Heirs, interspersed with both Yorùbá and English language. Still, the actors and actresses included popular skitmaker Kemi Ikuseedun, also known as Mummy Wa—who features as the lead actress and who is no stranger to the production of the stereotypical Korean depictions in many reels and short-form videos, and veteran Nollywood actor Chinedu Ikedieze who grew to fame for his comedic roles as Aki in the many movies he acted alongside Osita Iheme also known as PawPaw.

Anyone who is even remotely aware of the Nigerian culture and the experiences of secondary school students in a typical boarding school knows there’s little about this movie—if it can be called that—that speaks to the common Nigerian school stories, which have inspired movies such as The Origin: Madam Koi-Koi, a 2023 Nollywood two-part horror film produced by Jay Franklyn Jituboh and Dale Falola. Even if common themes like bullying are present in both cultures, representation is different because of how social dynamics differ from culture to culture.

For many Nigerians, the idea of a movie in Korean was laughable as many shared and stitched on TikToks and reaction videos, especially since the culture and mannerisms depicted weren’t something that the average Nigerian happens to experience in daily life.

How did Koreans react?

The general responses from those who shared online were love and fascination for the movie, and occasionally, defence of the Nigerian actors for the endeavour.

I had initially wondered what the reactions would be like upon seeing one’s own culture being portrayed by people who were not affiliated in any way. But after a few TikTok reactions and the movie making its way onto news outlets like JTBC, KBS and AllKpop, many of the responses professed their love and appreciation for non-native speakers speaking and acting in Korean, portraying the typical Korean school story, and the use of the typical accompanying music.

It shouldn’t have been surprising. The flattery of seeing your language and culture adopted by others is a privilege only experienced by those who do not experience the negative consequences of misinformation, misrepresentation and discrimination in the culture that is doing the adopting.

Cultures exchange and expound on one another, however, issues arise when people from various cultures are discriminated against by a lack of any or proper representation, and prejudiced laws and structures that uphold discrimination.

When schools and workplaces punish people of African descent for wearing their afros and kinky textures out, or for not adapting to the norm of silky, straight hair textures but the same textures are seen as a beauty trend when adopted by Asian or white people who very often do not attribute, or choose to remain willfully ignorant about the cultures from which they admire or adopt certain practices from, the kinky hair texture becomes a tool that signifies liberation from stifling norms.

When dances and manners of speaking are looked down on for being ghetto or razz when done by certain people, but become genius and groundbreaking when done by others, dances and languages become tools of recognition and representation of a culture that is often erased or overlooked in its contribution to the global space.

In cases like these, it can take effort to build awareness among the people being discriminated against of their misrepresentation and lack of representation, because it is so normalised to not see representations of yourself that it now becomes the truth.

Because it is normal for instance, for women to be absent from world leadership, or for Africans to be absent from stories about the creation and evolution of world histories and current events, it can be very easy to conflate identities in the dominant stories that exist. When someone from a minority group watches movies by a dominant group that portrays savages as uncouth and detrimental to “civilisation,” do you identify with the ones doing the naming or the people being labelled as savages? This phenomenon appears even in more modern examples when women who have been robbed of owning their pleasures, bodies and desires identify with the male perspectives of desire that are dominant in pornographic content, by looking through the lens of the man which objectifies women who look like them.

The ownership of culture and its representation then becomes, not a mandate that everyone has to follow because there are already dominant, single narratives that exclude you or to which you do not belong, but a small space that is intentionally carved out to cater to the full expressions of minority groups, who are denied complexities everywhere else.

As such, if there are 99 places out of a hundred where African stories are absent or are not told in their entirety, it is within the right of the culture being discriminated against to gatekeep and protect their culture and its representation from appropriation or erasure in the one remaining place.

Is this the first time an Asian culture is portrayed in Nollywood?

In 2020, I was happy to watch Namaste Wahala (which means 'Hello Trouble' in languages from both India and Nigeria), a cross-cultural romantic comedy film produced, written and directed by Hamisha Daryani Ahuja.

I thought it was a well-done story that brought together the two cultures in familiar tropes of having a wedding to plan, love and acceptance, and the various cultural treats many are accustomed to through India’s Bollywood and the presence of a large Indian community in Nigeria and vice versa.

So what went wrong with My Sunshine?

The absence of any Korean cast, poor integration of the Korean language and culture, and lack of a cohesive storyline which had more to do with the lack of a reason or cultural basis for the story. The reason for the movie was wrapped up in a statement made by veteran actor Chinedu Ikedieze (Aki) who starred as the founder of the Korean school that formed the centrepiece of the movie. His bold acclamation that “Korean is the greatest language in the world” raised more questions about who the sponsors and target audience were for the movie than it did to ground the story.

While the movie claimed to be the “1st Korean-Nigerian movie,” people soon discovered the Nollywood movie My Wedding by Tosin Olaniyan, released 6 months before, which integrated Korean cultural elements into a Yorùbá setting. In contrast, My Sunshine lifted both story and mannerisms prevalent in Kdramas to tell a Korean story, not just as a replication or for theatre, but as a Nigerian story.

Cultural exchange or profiteering?

With the proliferation of afrobeats in European and American countries, more Western celebrities and acts are collaborating with Nigerian artistes on their musical endeavours, which has led to the genre filtering its way to Asian audiences as well.

In 2021, Bolo by 페노메코 (PENOMECO) went viral for the afrobeats-infused song which also saw the artistes speaking Nigerian pidgin. There are one or two Asian acts are also popular for making short-form videos that lipsync afrobeats music and depict mannerisms commonly found in Nigerian music videos.

On the other side, Nigeria ranked 5th globally as the country that watches the most Kdramas in 2023, only outranked by the Philippines, Egypt, Malaysia and Indonesia. This has led to their portrayal in skits and movie depictions. Even more, Nigerians are currently exploring Korea’s culture through its food, pop music and dramas, as restaurants, classes and shows pop up to satisfy the demand.

There is no exchange if only one culture benefits

While there have been a few depictions of Afropop or African references in Asian media, even fewer tie back to their origins, leading to situations where African culture and acts continue to remain relatively unknown despite the occasional consumption.

Back to the movie, some people, both on the Nigerian and Korean side, touched on the problematic, heavily, one-sided nature of this cultural appreciation appropriation. Still, I found that on the Nigerian side, while a handful of reactions mentioned this fact, more often than not, reactions were incomplete and included the mockery of the accents—which led some Koreans to wrap up every unfavourable reaction as bullying.

While the Koreans responding may have missed the memo that African countries regularly engage in banter or roasting between themselves such as the famous jollof wars between Senegal, Ghana and Nigeria, the love for amapiano vs hate for xenophobia between Nigeria and South Africa, as an indigene of Igbo tribe who grew up without speaking the language and attempted to learn it later only to be mocked for my accent, I could not completely dismiss the bullying claim.

It is easy to get wrapped up in the petty conflicts that arise from minor differences within discriminated groups, where individuals fight to embody the best representation of a group in an effort to preserve their indignation at the cultural erosion and a reality that marginalises them.

For Igbos who had been laughed at for speaking English with the accent of their mother tongues, hearing someone speak their native language with the accent of a foreign language was something to grab onto and say “this is where I am better than you.” And yet, the common evil, the fact that Igbos were discriminated against for speaking their language to the extent that parents stopped teaching their children to speak their native tongue, went unaddressed.

For Africans whose direct lineages experience the worst of enslavement, encountering Africans who immigrate to various countries and who very often do not encounter or are not aware of racial trauma in the way that African descendants of slaves are can elicit the feeling that opportunities belonging to you are being taken, while Africans compete to be the model minority group, and yet, the common evil, that of discrimination based on the colour of skin, remains.

It takes seeing beyond the immediate conflict to gain the perspective needed to welcome everyone and stand together—despite unfavourable personal experiences—against the overarching problems of racism, cultural erosion, ignorance, and misrepresentations which affect everyone.

On the Korean side, there was disingenuity and a refusal to engage in or address any other narrative apart from the chosen—bullying, which was compounded by ignorance of African cultures.

In one breath, there was an admission of the lack of proper representation of Africa in much of Asian media and an acceptance that Korea was gaining cultural power and yet on the other, there was a denial that any culture was being exchanged by speaking a language.

I particularly found it interesting that the people who experience a lack of information on the multiplicity of African cultures and the representation of Africa as a country/monolith in their media can tell Nigerians what to think about the erasure of Nigerian stories and representation of foreign mannerisms in their own media industry.

The view that Nigeria’s Nollywood now has the chance to gain popularity with a movie like My Sunshine which portrays Korean culture contradicts how Korean dramas captured audiences worldwide.

Were Korean dramas portraying American realities? Did they speak a language they barely understood to an audience who did not understand? and would Korean culture have made the advances it did by simply copying the mannerisms of their Western counterparts rather than adopting them to suit their narratives?

If Hollywood decided to make a movie in the Korean language with only American actors while taking everything associated with Kdrama, would that still be commended by Koreans, and if not, why does one case bring about ego boosting while the other brings about serious cases of appropriation?

Nigeria is not new to adopting cultural elements such as from Hollywood celebrities in Nollywood, however, the stories have remained authentic to Nigerian experiences, and this is one of the factors that resulted in Nollywood becoming globally recognised as the second largest film producer in the world, and is popular in anglophone West-Africa, where Nigeria accounts for the largest share of revenue generated by film industries within the region.

The race for global superpower domination

As Western countries grapple with the realities and downfalls of a system built on extortion and extraction, it seems that more people are locked into the race for global superpower domination than they are to ensure not to repeat the mistakes of the past and the present.

In a system where the prosperity of a people is marked by how much power one can accumulate without respect and dignity, we only aspire to maintain the hierarchies that we were once so oppressed by once we begin to accumulate.

For a long time now, Africa has been “rising.” Africa has been next, emerging, and the future, but this story only works when you approach the continent as one that has never been developed, never been civilised, and as one that has always been backward and unstable.

If civilisations, such as the Benin and Dahomey kingdoms, are recognised for the advanced civilisations that they were—before people were captured, and art and resources stolen and deposited in museums and for industrialisations around the world, then a different story begins to unfold.

A continent and its people cannot devour itself while succeeding at the same time, only individuals on the continent can benefit within this system, and while colonisers can extract resources that “develop” their economies, Africa will continue to be a “rising” continent as long as its people and resources are diverted to developing and investing in everywhere else except itself.

Meanwhile, Africa has been the past and is still the present. Africa has been self-sufficient before being crippled into dependence, and every so-called “1st world civilisation” can be traced to its people and resources. The fact that African economic challenges continue to be taken out of this context allows for continuous exploitation and unawareness.

Is it all fun and games?

As Asian and Russian interests continue to seek staying power on the continent, more African countries prove uninhabitable as the standards of life depreciate for Africans residing in Africa. From Nigeria to the Congo, to Sudan, more people seek to leave for places that provide better opportunities as governments and leaders continue colonial interests of exploiting resources for personal and external gain.

With this, I understand the need for any Nigerian/African to abandon their “Africanness” at the expense of being looked upon favourably by places that they imagine they’d have better chances in, despite the multitude of unique challenges that African migrants face around the world.

The circumstances where veteran Nollywood actors are unable to pay their hospital bills would explain why Ikedieze, a veteran actor in the Nollywood industry, was cast in a role that boldly proclaimed Korean as the best language in the world.

It would explain why there is a lack of this enthusiasm for other African languages in the continent where it is still more expensive to fly to neighbouring countries than to London. It would explain why despite various tribes living together for over a century due to British amalgamation, no tribe has tried to make a movie depicting their admiration of each other, felt inspired by neighbouring countries enough to speak their language, or felt the need to depict minority groups favourably. I imagine that a venture like this would have gone a long way during the 2023 general elections where anti-tribal sentiment was a driving force in garnering votes.

Meanwhile, the speaking of one’s native language has been recognised time and again for being more than just a string of words, but an embodiment of a people, their identities, culture and their histories. This recognition tends to be made light of or dismissed when convenient for the party that stands to benefit the most. Whether made light of, misconstrued or recognised, the presence or absence of a people’s language, and by extension, their identities and cultures, continues to affect people till this day.

With the British introduction of English schools that were and still continue to be seen as beacons of intelligence, Africans are still discriminated against for speaking their languages and seen as daft or completely illiterate when they do, whether it is at schools where curricula founded on colonial legacies continue to be taught, or abroad due to racism.

With the British introduction of the Christian missions, native names were not accepted for baptism and other practices in the Catholic church because only English names were affiliated with sainthood.

In Nigeria, there are still people who do not speak Igbo because parents worried that their children would sound “igbotic,” a term that captures speaking English with a heavy Igbo accent, especially after the Biafran-Nigerian civil war.

During the Japanese occupation of Korea, Koreans were banned and often punished for speaking their language to the extent of enforcing the change Korean names to Japanese names. And during the transatlantic chattel slave trade, Africans were deliberately mixed with other tribes so that they could not communicate with each other in their languages.

While people learn languages for all sorts of reasons including, immigration and admiration, it matters whose language is being spoken because it is in a people’s best interest for the world to speak their language and imbibe their cultures—this is why countries increase their diplomatic efforts to ensure a positive image in countries of interest. In addition, there are very real biases to the languages learnt, where a polyglot speaking Kiswahili, Hausa, English and Twi is not considered impressive, but a polyglot speaking English, French, Mandarin and Italian is considered cool and amazing.

Ravaging capitalism and the business of media

There’s this misconception that Africans cannot tell our own stories, and that we do not find our stories fascinating enough to consume.

The reality, however, is more grim. African film industries like Nollywood are consistently underfunded that taking on high-quality projects and even gaining the rights to our music becomes an expensive venture that adds up. The people for whom the stories are created cannot pay, and the people who can pay, usually Western production houses, often place demands that change the story to appeal to the Western taste, thereby changing the story's authenticity.

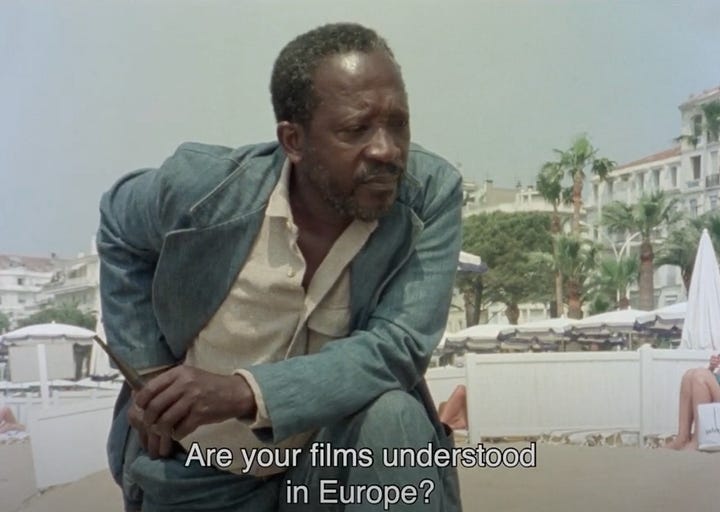

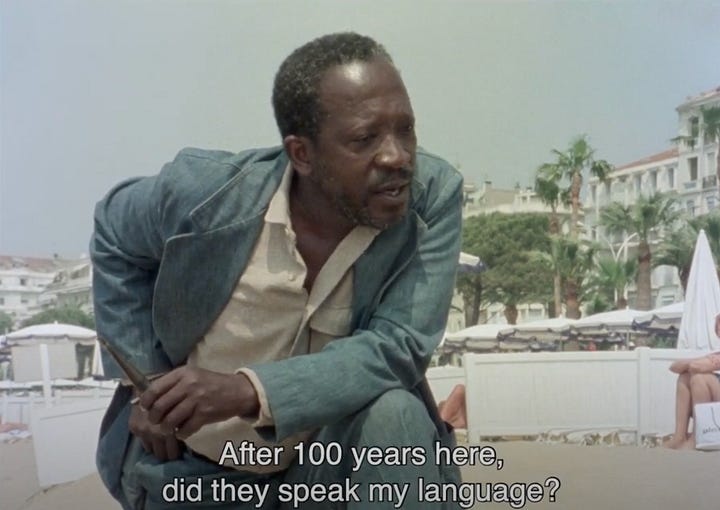

The effects of this are also seen in the literary world littered with African authors fighting to write beyond war, poverty, and conflict. The subject of African cinema appealing to, or being validated by foreign interest is something that Senegalese author and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, often referred to as the father of African film, touched on in an excerpt from an interview Filming Against All Odds, which continues to reverberate across time.

I find this particularly telling as more African stories, some of which were recommended reading growing up, interpreted and told through the lens of African experiences—which colonialism is a big part of, are now being visualised with Americanised projections that do not capture the essence of these stories, for the ultimate gain for more visibility or exposure.

Movies like Marvel Universe’s Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, and the adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, despite stunning visuals, have left audiences thinking that Wakanda is a real place, identifying with a fictional idea of an “African motherland” when there are real places like DR Congo where people are still fighting conditions resulting from the forced extraction of cobalt, and have washed down a powerful story of the Biafran-Nigerian war and ethnic cleansing that left tens of thousands of people dead and missing, a story which is still difficult to address and is not commemorated till today in Nigeria, with characters that do not, cannot embody the depth and history that continues to exist on the fringes.

And yet, this trend only gains ground. The recent foray to adapt Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, first published in 1958, to the screen by the American production studio A24 has torn people between the joy of an Igbo story being told on a global stage and the absence of any other Igbo people in the casting and direction. The critically acclaimed novel tells the story of Igboland’s precolonial era and the arrival of European missionaries and colonial soldiers. The novel’s protagonist, Okonkwo, previously portrayed by famous Nigerian actor Pete Edochie in both the 1971 film adaptation and the 1987 miniseries, will now be portrayed by the British actor (of African descent) Idris Elba.

I imagine it would be difficult, even for a Ghanaian actor living in Ghana, to portray a cultural moment anchored in the customs, language, nuances and experiences of the Igbo people, much more one who has little interaction with the culture and continent as a whole.

Update: Earlier this week, Idris Elba announced his plans to move to Africa ‘to bolster the film industry’ and make African films that ‘own those stories of our tradition, of our culture, of our languages.’ With his production company 22Summers, plans to live in Ghana’s Accra, Sierra Leone’s Freetown, and to build a studio in Tanzania’s Zanzibar, I’m thrilled about the potential impact this move will have on African cinema and its global reach.

The media has been responsible for some of the most gruesome stories about Africa and Africans. Till today, some people ask borderline racist questions or make negative comments about how Africans live, straight out consider ways of life different to theirs as inferior to themselves and their culture, or continue to use broad strokes that represent Africa as a monolith.

For Americans, the media has been responsible for the proliferation of American ideals. The idea of “living the American dream” was so prevalent that its visa became one of the most demanded in the world. Kdramas and the demand for Korean content also follow this trajectory. Koreans have been able to cultivate the power of the media to grow their proximity to Western media and by extension to every other part of the world that consumes Western media.

As more Nigerian and other African stories are Westernised for exposure, and the Nigerian actors now speak Korean for visibility, what is being made visible?

If the stories being told bear no resemblance to the stories of ourselves, or the stories we know and love, and we begin to tell the stories of others, what is being told of the people and the land?

What looks like hustle and creativity on the surface, turns into the capitalisation on media to make businesses out of, or for individuals to be recognised by foreign interests in order to leave or abandon a place that continues to be dominated, colonised and exploited for personal gain.

It turns into a story of placelessness, where every situation either presents an opportunity to leave for greener pastures and if it doesn’t, is abandoned for the next thing that does.

The underlying story is one that speaks to ongoing exploitation, the loss of a place and culture that people once felt connected to as indigenes, but which is now traded in competition for scarce resources and opportunities.

Telling Nigerian stories

Desire drives imitation, whether it is the desire to capitalise on businesses that the Kdrama industry brings or not, which leads me to shed light back to the stories we tell of ourselves as Nigerians. Are the stories we tell inspirational enough?

For the most part, Nollywood has been filled with fear-mongering from religious houses, individual success against all odds, the demonisation of single women, and many other attributes typical and symbolic of the authoritarian relationships between authority figures like parents and pastors and their children and congregation.

To adopt a completely new culture—to desire and be inspired enough by it to learn the languages of people living half a day away in time—is no small feat. Especially considering that the genre of Kdramas tends to represent communication and emotionality in an indirect, soft-natured way that is not typically represented in Nigerian culture and movies.

If Nigerians, who are stereotypically loud, can relate to common themes of love and jealousy portrayed so differently, then rather than presenting a caricature, we can tell more stories that go beyond the portrayed aggression and lack of sensitivity that reinforces black people as strong and not deserving of softness. Rather than reinforcing ideas that black people can only be seen with more complexity when they completely adopt other cultures, we can tell stories that validate black women who are soft-spoken, that protect black men who have embraced their femininity, and bring sensitivity rather than violence to African women in the name of love. More importantly, we can address the blockers that get in the way of these expressions in our own cultures, by bringing socio-economical issues to the forefront in the stories we tell, just as they are done in Kdramas.

While Nollywood has made and continues to make waves, there are still challenges to actors & actresses being acknowledged on the global stage and to African stories being represented without being stripped of their authenticity and being crippled before being given a chance to fly.

Just like Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart was translated into over 60 languages and made an impact big enough to inspire a Hollywood adaptation, we can begin to include more people in a way that doesn’t offer flattened narratives for mindless consumption for global visibility.

Equal to the need for better funding, we need more of our stories to inspire reflection or actions that foster curiosity about our lives and the lives of others different from us, who live close to us and in neighbouring countries, so that we can start to reposition ourselves beyond our local contexts, beyond the local understanding of our environments, beyond our geographical boundaries, in a way that embodies ourselves and our stories fully.